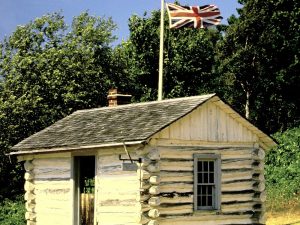

Welcome to your digital tour of Discovery Harbour

Step into the past with our digital tour of this 19th century British naval establishment! Throughout this tour, you’ll find detailed descriptions and information about the site’s history, accompanied by captivating photos and audio clips. Enjoy your tour!

Welcome to Discovery Harbour

1817 – 1856

Situated along beautiful Penetanguishene Bay, this picturesque historic site is a reconstruction of an original 19th century British naval and military base. Originally conceived during the War of 1812, the actual construction of a Naval Establishment would have to wait for peacetime. Becoming operational in early 1817, the base served as an important supply link to more northerly British outposts, and safeguarded gifts destined for Britain’s indigenous allies. A naval dockyard cared for a wide variety of vessels, both active and decommissioned. Small detachments of soldiers were sent to Penetanguishene to support the operation.

Though the Naval Establishment had grown to house over 70 people by 1820, financial reductions during the ensuing few years greatly reduced the Naval operation to only a handful of core personnel. In 1828, a British garrison on Drummond Island was relocated to Penetanguishene, and it became a Military Establishment as well as a Naval one. In 1834, the British Navy withdrew completely from Penetanguishene, leaving the facility solely to the care of the Military, who occupied the site until 1856.

Your tour begins in the naval portion of the historic site and proceeds northward to the military. While no original structures remain from the Naval Establishment, its reconstruction is derived from historic documents, and an attempt has been made to respect the original arrangement of buildings, representing the peak period of naval activity from 1817 to 1822.

In 1793, Upper Canada’s first Lieutenant-Governor, John Graves Simcoe, recognized the young colony’s vulnerability to attack. As part of an overall defence strategy, he identified the harbour at Penetanguishene as an ideal location for a naval establishment. Conveniently tucked out of sight off Georgian Bay, Penetanguishene Bay’s length and depth was well-suited for accommodating large vessels, and the multi-leveled hillside was ideal for defensive construction.

The War of 1812 highlighted the British need to secure supply lines to northwestern outposts and ensure their superiority on Lake Huron. In late 1814, preparatory work began for the construction of a naval establishment – but did not last for long. The signing of the Treaty of Ghent in late December of 1814 ended hostilities between Britain and America. When this news reached Penetanguishene in March of 1815, all work at the outpost ceased and all personnel were redeployed.

But post-war tensions caused concern about maintaining defensive lines and supply routes on Lake Huron. Construction of the Penetanguishene base once again became a priority, and it began operations in 1817. That same year saw British and American diplomats sign an accord known as the Rush-Bagot Agreement which restricted the number of armed vessels both sides could have on the Great Lakes. As a result, two British transport schooners, HMS. Tecumseth and HMS. Newash, required a harbour where they could be decommissioned and maintained in a state of “ordinary”, which meant that their hulls would be moored and maintained, while their guns, sails, and rigging would be stored and kept in a state of readiness. Both vessels were ordered to Penetanguishene in early June of 1817 and were put into ordinary by the end of the month.

With its original purpose slightly modified to accommodate peacetime needs, the Naval Establishment developed quickly. At its highpoint in 1820, the base’s numerous personnel included sailors, civilian workers, naval officers and their wives, and a military guard.

TOUR STOPS

1. King’s Wharf and Naval Storehouse

The Wharf was an essential location – the point of arrival and departure for all supplies and personnel.

The adjacent three-storey Storehouse contained the various supplies necessary to the Naval Establishment.

King’s Wharf and Naval Storehouse

The King’s Wharf provided the docking facility for the transport schooners carrying supplies and personnel on Lake Huron. Incoming barrels and crates would be handled by sailors and hauled to the Naval Storehouse for processing, while shipwrights could engage in effecting any repairs required.

At its peak in 1820, the Penetanguishene Naval Establishment was home to more than 20 vessels of various sizes, including the two decommissioned schooners, three active transport schooners, and a variety of smaller vessels.

Adjacent to the Wharf stood the Naval Storehouse, a large three-storey structure housing an 18-month supply of provisions, medical stores, bedding and clothing as well as various tools and hardware. All rigging and sails from the warships were maintained in the Storehouse, as were the ships’ guns and other small arms. It also stored a large quantity of goods destined for distribution as gifts to Britain’s Indigenous allies at the northern outpost at Drummond Island.

To safeguard assets, thorough inventories of all supplies entering and leaving the Storehouse were required. Quarterly surveys were taken of all stores to ensure their security and to monitor their condition. For added protection, the Storehouse was surrounded by a tall palisade, and was regularly patrolled by a military guard.

2. HMS Tecumseth

Except for one final voyage in 1819, armed transport schooner HMS Tecumseth lay in a state of ordinary near the Wharf.

HMS Tecumseth

Launched at Chippewa in September of 1815 and named in honour of the renowned Shawnee chief and ally of the British, HMS Tecumseth spent two years transporting troops and supplies on Lake Erie. She was rigged as a topsail schooner, and her defensive equipment included two “24-pound” cannons. HMS Tecumseth had only just been transferred to Lake Huron in the spring of 1817 when the Rush-Bagot agreement caused her to be laid up at Penetanguishene by the end of June. After being re-rigged for one transport mission in 1819, she was returned to a state of ordinary and never sailed again. By 1828 HMS Tecumseth had sunk off the shore of the Naval Establishment where her hull remained until being recovered from the water in 1953. You can see these original hull remains in Discovery Harbour’s HMS Tecumseth Centre.

The replica of HMS Tecumseth was begun in 1992 and completed the following year. In 1994 the vessel received an historic warrant officially reinstating her as an honorary ship in the Royal Navy. The replica measures 38 metres overall, on-deck length is 21 metres. Her beam, or width, is 7 metres. Fully rigged with her topmast she achieves a mast height from the deck of 32 metres, as you currently see her the mainmast height from the deck is 18 metres.

3. HMS Bee

Of the three small transport vessels active on Lake Huron (Bee, Wasp & Mosquito) the Bee served the longest.

HMS Bee

Built at the British naval depot at the Nottawasaga River (near present-day Wasaga Beach), the original Bee was one of three transport vessels operating from the Penetanguishene Naval Establishment. The Bee was rigged as a gaff-topsail schooner to enable her to negotiate the waters of Lake Huron as she ferried supplies to various destinations. Following an assignment as conveyance to John Galt in 1827, Bee was listed as “requiring thorough repair” while her two sister ships, Wasp and Mosquito, already out of service, were described as “completely rotten”. Though all three vessels were put up for auction in 1832, their final fate remains unknown.

The replica of HMS Bee was launched in 1984 and received an historic warrant reinstating the vessel as an honorary ship in the Royal Navy. The replica measures 29 metres overall, with an on-deck length of 15 metres. Her beam, or width, is 4.5 metres. As you see her, including her topmast, the mast height from the deck is 15.5 metres.

4. Smaller Vessels

Types of small boats found at the Establishment were gigs, jolly boat, skiff and flat-bottomed bateaux.

Smaller Vessels

A variety of smaller vessels were part of the establishment’s contingent during the naval time.

Gigs

Described as light narrow clinker-built ship’s boats, gigs normally ranged from 5 to about 10 meters in length. Often equipped with small sail rigs they could be rowed with four, six or eight oars depending on size and purpose. Gigs were sometimes the private property of a captain or commander and were common vessels in Upper Canada.

Jolly Boat

A jolly boat was usually a ship’s boat, with a bluff bow and wide transom, often hoisted at the stern of a larger vessel and used for small work. They earned the nickname of “blood boats” from the practice of using them to transport fresh meat from shore to ship. An average jolly boat was around 5 metres in length with four oars, and the capacity to be rigged with a small mast and sail.

Skiff

At around 4 metres in length and smaller than their jolly boat counterparts, skiffs were usually two-oared vessels adaptable for sailing. They often served as ship’s tenders, being more suited for the ship-to-shore transport of important personnel.

Batteaux

Excellent in shallow waters, flat-bottomed batteaux were used extensively as transport vessels by both the Navy and Military in Upper Canada. Those stationed at Penetanguishene averaged around 11 metres in length, and likely required six oars with an additional oar serving as a make-shift rudder.

5. The Dockyard

The ongoing maintenance of buildings and ships was centered in the dockyard area and manned by a hired civilian workforce.

The Dockyard

As the central work area for the maintenance and repair of the ships and buildings, the Dockyard was the main hub of activity at Penetanguishene. Although smaller than some of its other Upper Canada counterparts, it nonetheless featured key elements common to larger British dockyards. A civilian workforce of sawyers, shipwrights, blacksmiths and oxen drivers were hired on contract by the Royal Navy to provide the labour to keep vessels afloat and buildings maintained. The dockyard consisted of a sawpit, steam kiln, naval slip, and blacksmith shop.

6. Sawpit

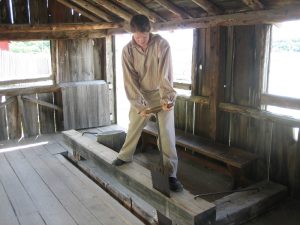

All the planking needed for vessels and buildings alike had to be laboriously sawn by hand by a team of sawyers.

Sawpit

In this covered shed, sawyers used a pit saw to cut squared timbers into planks for the Navy’s ships and buildings. One man stood on top of the log and used a tiller-like handle bolted to the saw blade to control its direction and ensure a straight cut. The man in the pit below used a cross-handle to draw the saw down through the wood for the cutting stroke. These men could produce roughly 45 metres of softwood board (or 23 metres of hardwood board) in a day’s work.

7. Steam Kiln & Naval Slip

Shipwrights steamed planks or effective fitting on vessels hauled ashore on the slip for repairs.

Steam Kiln & Naval Slip

The curvature of ships’ hulls required the bending of planks to properly fit them into place; the Steam Kiln allowed for this to happen. Planks were placed in the wooden boxes (nicknamed coffins) and water in the iron boilers was heated by fires to create steam. The planks absorbed the heat and moisture making them pliable so they could be fitted and clamped in place without breaking.

While large vessels were required to be at the main wharf for repairs (and were severely tipped to one side to do so), repairs could be made to smaller vessels, hauled up on a naval slip. Once the newly fitted planks were secured, the seams were then caulked with oakum. Made from old rope fibres and pine resin, oakum was laid in the seams and struck tightly into place using a chisel-shaped iron and a wooden mallet. It was then sealed over with pine tar to complete the process. A similar technique, called “chinking” was used on buildings with a mixture of clay and straw to fill in the gaps between logs.

8. Blacksmith Shop

Two blacksmiths shared a small workshop to produce the ironwork required for ships and buildings.

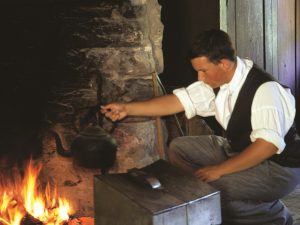

Blacksmith Shop

Two blacksmiths were responsible for all ironwork at the Naval Establishment. Fueling a charcoal fire with air fed from hand-pumped bellows, they heated iron until it was soft and malleable. They then shaped the iron on the anvil with hammers and a variety of other tools. The work was often repetitive, such as the production of hundreds of hand-wrought nails. Sometimes the tasks were more challenging, like the forging of specific bolts and fittings for the vessels. Occasionally the work required more intricate skills, such as repairing the working parts of a musket.

9. Métis Dwelling

Métis peoples often served as guides, letter carriers and vital cultural intermediaries between the British and indigenous populations.

Métis Dwelling

During the naval time period, early Métis peoples (of European and Indigenous ancestry) served as vital cultural intermediaries between the British and indigenous populations in Canada. Frequently they were hired as guides and interpreters for the British navy and military, work which took them away from their homes for extended periods of time. While employed at Penetanguishene Naval Establishment these individuals were frequently quartered in the Sailors’ Barracks.

In 1828 the British strategically relocated their military base from Drummond Island to Penetanguishene (see Stop 20 for full details). Accompanying the British forces on the move was a civilian component of about seventy-five families, many of them Métis. Settling on grants of Crown land in the Georgian Bay region, they formed the nucleus of the burgeoning community of Penetanguishene. They continued to serve as guides and interpreters, as well as providing skilled labour to the Military base as blacksmiths, builders, bakers and clerks.

10. Quarterman’s Office

Quarterman of Shipwrights Robert Adams supervised the dockyard operation from this combined office and workshop.

Quarterman’s Office

Overseeing the work of the civilian dockyard personnel was the Quarterman of Shipwrights, Robert Adams. The term “Quarterman” derived from the practice of dividing a ship into quadrants for repairs, but at the smaller Penetanguishene operation one such position had to suffice. Adams’ main role was to keep the vessels and buildings in a good state of repair. To ensure materials and tools were available, periodic surveys of each vessel including work and cost estimates were completed.

Assigning tasks and tools to the men, Adams would supervise their efforts and participate in the work as needed. Of great frustration to Adams was the bureaucratic process involved in requesting materials and funds from England, and the slowness of communication meant he often estimated his needs up to a year in advance.

Notice the variety of tools in this workshop; they provide an idea of the broad scope of tasks for which the Quarterman was responsible.

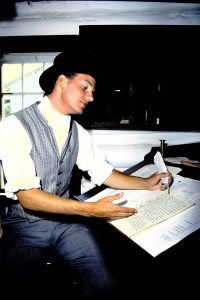

11. Office of the Clerk-in-Charge

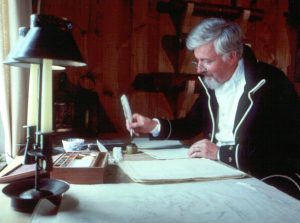

Clerk-in-Charge George Chiles managed the day-to-day administrative tasks for the base, including attendance, wages, and provisioning.

Office of the Clerk-in-Charge

The civilian position of Clerk-in-Charge was the efficient running of a remote outpost. The Clerk was responsible for the regular mustering (rollcall) of the men, marking all entries and discharges in the books, as well as completing bills and pay lists. Quarterly, he had to travel to York (now Toronto) to receive money for payment of wages and subsequently ensure that they were properly disbursed. The Clerk supervised all aspects of provisioning and issuing supplies, including the regular survey of items in the Storehouse. The Clerk also kept records of all transactions and official business at the Establishment, consistent with the administrative structure of larger dockyards in the empire.

The small office provided by the Navy gave the Clerk a workspace away from his home and close to the Yard. Its importance is notable since it was the only separate office space granted to any of the Establishment’s personnel.

At Penetanguishene, the Clerk position was held by George Chiles, whose qualifications and dedication were demonstrated in the high praise given him by the officers of the base.

12. Sailors’ Barracks

Repairing ships’ rigging and sails, chopping wood and even gardening, the sailors of the Establishments took meals, socialized and rested in the communal Barracks.

Sailors’ Barracks

A regular complement of six sailors was posted to Penetanguishene. Life on land posed many challenges for men used to shipboard routine. Still responsible for the maintenance of the rigging and sails of the decommissioned transport schooners, extra tasks included felling timber, cutting firewood and tending gardens. Shipboard routine was continued through the Naval practice of issuing rations and assigning daily work duties.

All daily supplies were rationed out: candles, wood, clothing and food. The staples of the sailor’s diet were salted beef and pork, dried peas, biscuit, and grains such as oats. Additional rations included cheese, tea and coffee, chocolate, rum and beer. Fresh vegetables from the Establishment’s gardens were a welcome addition. A typical day’s meals might be a breakfast of oatmeal with biscuits, a lunch of bread and soup and a dinner of stew.

Accommodations for the six sailors were more spacious in the Barracks than aboard ship, but only during the summer. In the winter months the survey crew working for Lieutenant Henry Bayfield was quartered there as well. The building served as shelter, dining area and a place for recreation.

Leisure activity for the sailors often included games of chance such as “quoits”, played by tossing rope grommets at a board of nails on the wall or at a peg in the floor. Wagering was frequent and involved items such as food or rum rations, clothing, or shoes. Escape from their difficult, isolated situation led some sailors to drunkenness or even desertion. In spite of the harsh conditions and difficult life, these skilled men played a vital role in the defensive plan of British Canada.

13. Assistant Surgeon’s House

Serving on land meant that Assistant Surgeon Clement Todd mainly had to treat insect bites, cuts and bruises, poison ivy, and frostbite.

Assistant Surgeon’s House

Assistant Surgeon Clement Charles Todd was posted to Penetanguishene in 1819. Todd’s role on land was the same as aboard ship although the medical situations he faced were slightly different: insect bites, poison ivy, frostbite and a variety of cuts formed the bulk of his workload. Following their marriage in 1821, Todd was joined at Penetanguishene by his wife Eliza.

Common treatments in the early 19th century included bloodletting by lancet or leeches, and the preparation of pills and medicines. Medical practice was still driven by myth and tradition and was only slowly developing along scientific lines. Todd himself displayed a keen scientific curiosity – he was an avid botanist, identifying and classifying many plants common to the region. Todd also accurately compiled meteorological data, creating a detailed record of the climatic conditions at Penetanguishene.

A notable visit occurred in 1825 when explorer Sir John Franklin made a nine-day stopover at Penetanguishene on his way to a second Arctic expedition. Franklin was impressed by the small Establishment and recorded much about its location and organization in his journal. Franklin was particularly impressed with Clement Todd’s meteorological work and would later include it as an appendix to his book about the 1825 expedition.

14. Home of the Clerk-in-Charge

For George Chiles, the ability to entertain occasional guests was an appreciated advantage at this remote outpost.

Home of the Clerk-in-Charge

The accommodation provided to George Chiles was quite reasonable for the standards of the day and was on par with any given to the officers of the Establishment. The ability to entertain guests, few as those might be, was certainly an appreciated advantage in a remote location. His home was also a welcome refuge from the long hours spent in the naval Yard, and a place where he could write personal letters to his family back in England. Chiles spent five years at Penetanguishene, returning to England in 1822.

15. The Stable

The higher-ranked personnel at the base were allowed small agricultural luxuries such as a stable and chickens.

The Stable

Those occupying positions of authority were afforded certain luxuries; details of the original Naval Establishments indicate extra out-buildings around a home are one such example. Separate kitchens were common for those higher up the command structure. Storage sheds and outdoor privies were also common advantages. Stables were known to have existed for the Captain and the Clerk and may have been built for other higher-ranking personnel as well.

16. Cemetery

Dating from the military period, the graves of two soldiers and a young girl serve as a reminder of the harshness of life in the Canadian outback.

Cemetery

These grave markers are from the site’s military period and serve as a solemn reminder of the sudden harshness of life in the Canadian outback. Soldiers (and brothers) John and Samuel McGarraty perished from exposure to the elements while on the long march to the Penetanguishene base from York (now Toronto). The second marker identifies the grave of a young girl named Roseanna McCabe; we do not know with certainty her background or how she died.

17. Commanding Officer’s House

Captain Samuel Roberts

Roberts’ wife Rosamond

The Commanding Officer supervised all aspects of the Establishments’ operation.

Captain Samuel Roberts served from 1819 to 1822, accompanied by his wife Rosamond and her sister Letitia.

Commanding Officer’s House

The role played by the commanding officer of the Naval Establishment was varied. Serving from 1820-22, Captain Samuel Roberts was required to supervise all aspects of the operation, function as a magistrate, discharge any misbehaving sailors, and report any misconduct of officers. He also had to approve estimates and transactions. Additionally, Roberts was to familiarize himself with the work being completed by hydrographer Henry Bayfield, specifically any information relating to American activity on the Great Lakes.

Roberts was accompanied to Penetanguishene by his 21-year-old wife Rosamond and her 19-year-old sister Letitia. The ladies found little refinement in the rugged backwoods setting. Their journey to Penetanguishene was challenging; five of their seven sleighs of belongings were lost through the ice, and upon arrival at the Establishment found the accommodations well short of their expectations. Yet the Roberts family formed the centre of a small social circle. Trained in the fine arts and the skills needed to successfully host social gatherings, the ladies did their best to maintain a level of comfort.

A sore point for Captain Roberts was the inconvenience of having to use his home as an office for conducting official business and planning operations. This sentiment was also felt by the ladies, who were required to retire to the back bedrooms whenever the Captain had work to do. In spite of these hardships, it is documented that Captain Roberts appreciated his posting in Upper Canada.

18. Commanding Officer’s Kitchen

The Commanding Officer was afforded a servant, who prepared meals and attended to housekeeping duties.

Commanding Officer’s Kitchen

The rank of Captain included certain privileges, such as having a household servant. This allowed the ladies to pursue genteel activities like needlework and artistic endeavours while the servant would clean the house and prepare the meals. The servant position was taken seriously, indicated by the rapid dismissal of the first two men appointed.

It was 21-year-old Richard Pye who eventually held the position. Since this young sailor from Ireland may have had little practical experience in matters of the household, he would have received direction from the ladies. The fact that Pye could read allowed him to use recipes – a highly valued skill. Food prepared for the Roberts household would have been of higher quality than many others at the base. While fresh vegetables were available from the naval gardens, many of the foodstuffs would have come from the supplies kept in the Naval Storehouse. For entertaining the Captain would have had access to his own collection of wine and spirits.

19. Naval Surveyor’s House

Hydrographer Henry Bayfield was based at Penetanguishene while conducting the survey of Lake Huron, assisted by young Midshipman Philip Collins.

Naval Surveyor’s House

Due to their poor performance on the Lakes in the recent war, the Royal Navy decided that more accurate charts were required for their commanders. Initiated in 1815, the Great Lakes Survey would gather the various data necessary to do so. At the same time, it would confirm the location of boundaries and collect information on American activities. Talented young hydrographer Lieutenant Henry Wolsey Bayfield was assigned to proceed to Lake Huron following his earlier efforts on lakes Erie and Ontario. During this new work, he and his crew were based at the Penetanguishene Naval Establishment.

Bayfield’s assistant was 16-year-old midshipman Philip Collins, and 16 able-bodied men served as boat’s crew. They worked from two 19 metre open gigs, in which they had to fit the survey equipment and supplies needed. The survey season began with the ice melting in the spring and ended in late autumn with its return. The hardships were great – difficult work in harsh weather conditions, a lack of regular supplies, and poor shelter. Oiled canvas overcoats provided some relief from the damp, and oiled bags protected their equipment. You can see these foul weather items hanging on the wall.

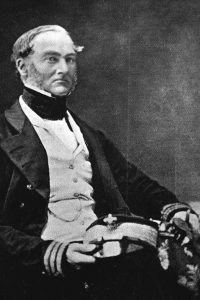

Henry Bayfield

Henry Wolsey Bayfield was born on 21 January 1795 in the town of Hull, Yorkshire country, England. The young Bayfield first saw Canada in 1810 when a vessel he was serving on, HMS Beagle, visited Halifax and Quebec. After a series of postings on other ships, Bayfield returned to Quebec in 1815 and in 1817 was given full command of the Lake Huron survey at the age of 22.

To quote Bayfield: “…it is my ambition to render this work so correct that it shall not be easy to render it more so”

The practice of naval surveying and chart-making, known as hydrography, was a relatively new science in the 19th-century, and Henry Bayfield was perhaps its most skilled practitioner. During the winter, while his crew was quartered in the Sailors’ Barracks, Bayfield, with help from his assistant Phillip Collins, transformed his notes into charts in the home provided on the base.

Bayfield’s work extended well beyond the Lake Huron survey and his time spent at Penetanguishene. He eventually surveyed the whole of the St. Lawrence water system, and much of the eastern seaboard. His distinguished career saw him retire with the rank of Vice-Admiral, and he spent his final days living in Charlottetown, Prince Edward Island. Through the eighteen seventies, the Vice-Admiral could be seen taking his daily walks through the streets of the town. It was written that “his distinguished appearance and kindly countenance gave him respectful recognition wherever he went.”

20. Transition from Naval to Military Establishment

Naval and Military establishments co-existed at the facility for six years. The Military Establishment would remain in operation until 1856.

Transition from Naval to Military Establishment

In passing the modern boat shop, you are transitioning from the naval period of the site’s history (1817-1834) to the military period (1828-1856).

Financial pressures in the wake of the War of 1812 finally caught up to the Royal Navy, forcing it to greatly reduce its operations in the Canadian colonies. The year 1822 saw the first of several cutbacks over the next dozen years, which saw operations severely diminished at the Penetanguishene Naval Establishment. After 1822, the naval personnel consisted of: 1 Lieutenant commanding, 1 Assistant Surgeon, 1 Shipwright, a Store Porter, 3 able-bodied men, and 2 Boys (2nd Class) as servants. Small military detachments continued to provide security and fatigue work at Penetanguishene, but ironically now outnumbered the naval contingent they supported.

During the 1820s, a British and American commission established by the Treaty of Ghent worked to formalize the borderlines between the two nations in North America. As part of that process, the British ceded Drummond Island, located in the northernmost part of Lake Huron, to the United States. This necessitated the removal of their military outpost there, and the whole garrison was transferred to Penetanguishene in late 1828. Accompanying the official military personnel in the move were some 70 civilian families, including Métis and Indigenous, who continued to provide the skills and labour required at the newly relocated garrison.

And thus, in 1828, Penetanguishene officially became a Military Establishment as well as a Naval one. Their coexistence was at first tenuous, as no advance preparations for the move had been authorized at Penetanguishene, and the incoming personnel were forced to make use of many defunct naval structures for shelter and storage. Lieutenant William Henry Woodin, the naval officer commanding, did his best to accommodate this significant influx while the military struggled to build its own infrastructure.

But while the Military Establishment slowly progressed, the Naval Establishment remained stagnant until finally ceasing operation in 1834 with the Royal Navy’s complete withdrawal from Upper Canada. Excess supplies and stores were sold off at auction, and the few remaining personnel were either discharged or redeployed back to England. The British Military now represented England’s authority in the Canadian colonies.

Military Organization

Identical to other British military establishments, there were six branches of the military working cooperatively under the general direction of the garrison commandant:

Regimental Detachment:

The detachments of soldiers stationed at Penetanguishene consisted of up to 60 men, usually with a lieutenant and one or two sergeants.

Adjutant General’s Department:

This branch was responsible for the arming, clothing and equipping of the troops, as well as recruiting, transfers, discharges, and discipline.

Commissariat Department:

This department’s main function was to supply the army with all manner of provisions.

Ordnance Department:

All other military needs were supplied by the Ordnance Department, which was also responsible for providing barracks.

Medical Department:

Providing medical care for the personnel of the base, this branch of the military was often staffed by one surgeon, working with soldiers delegated as assistants.

Indian* Department:

The personnel of this branch were specifically concerned with maintaining links to the Indigenous tribes allied with Great Britain, particularly those who had fought in the War of 1812.

* Please note that “Indian Department” is a historical designation, and the term “Indian” is not acceptable in modern usage.

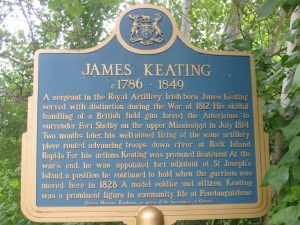

21. Home of the Fort Adjutant (Keating House)

Fort Adjutant James Keating managed the military establishment’s many bureaucratic functions. He lived at the base with his wife Jane and their five children.

Home of the Fort Adjutant (Keating House)

While regiments and commanders came and went at the Military Establishment, the Fort Adjutant was a constant presence at Penetanguishene, providing continuity from year to year. His duties included attending on the Commanding Officer to receive and implement the day’s orders, conducting military drills, inspecting the troops, and assuming responsibility for the appearance and instruction of non-commissioned officers and men. Bureaucratic duties included keeping the regimental orders and maintaining record books such as the Garrison Letter Book, a register of all marriages, baptisms and deaths that took place.

James Keating arrived as Fort Adjutant in 1828, accompanied by his wife and three children – two more were born during his stay at Penetanguishene. Within the home, the kitchen was the focal point of daily life, with Mrs. Keating cooking all the meals on the hearth and providing basic education to the children.

Despite some challenges, the Keatings still had many advantages over early settlers. Their house was built for them, the surrounding grounds were already cleared, and certain chores and provisions were provided by the military. The Keating family may also have maintained a herb garden. Keating’s salary as Adjutant allowed the family to entertain guests comfortably.

James Keating

James Keating was an active member of the Penetanguishene community. He was instrumental in the construction of St. James-on-the-Lines, the area’s first Anglican Church. In his later years, he also served as the local Superintendent of Schools for Tay Township.

James Keating died in 1849 and was buried in the cemetery at St. James-on-the-Lines. His wife Jane and the children continued to live in the home until 1856, when they moved away upon the closure of the base. The homestead stood for another half-century, burning to the ground in 1913. The present reconstruction is based on original photographs and is built around the original double fireplace and chimney.

22. Parade Square

Daily drill practice was a requirement for British soldiers to ensure their consistent performance in response to issued commands.

Parade Square

Daily drill was the most important part of the soldier’s regular routine. Drill practice ensured soldiers would respond consistently and accurately to specific commands regarding muskets, marching and manoeuvres. It was performed at least three times each day; extra drill could be assigned as punishment for poor behaviour or rule infractions at roll calls or inspections. The field central to the Military Establishment provided the large open space required for this purpose.

The soldiers were housed together in a large two-storey stone barracks which stood near the Officers’ Quarters. A military regulation permitted six out of every one hundred soldiers to have wives and children accompany them. At Penetanguishene this rule seemed to be relaxed, and there were often more women and children listed on the books than officially allowed. Over the years of occupation, an average of 50 to 60 people lived in the barracks; this number peaked in 1848 with 105 people composed of soldiers, their wives, and children.

The large structure was destroyed by fire in 1870, when the military property had become a Juvenile Boys’ Reformatory.

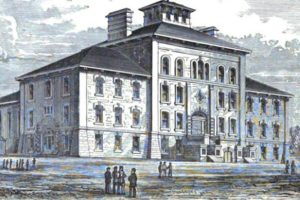

23. Original Officers’ Quarters

This luxurious residence was home to the Garrison Commandant and any junior officers. This original structure has been restored to its 1840s style.

Original Officers’ Quarters

The officer commanding the regimental detachment fulfilled the role of garrison commandant at Penetanguishene. The responsibilities of this position were to oversee daily garrison routine and ensure cooperation between the six military departments. The commanding officer also presided at the annual distribution of gifts to Indigenous allies and was responsible for ensuring the welfare of any military pensioners arriving in the area.

Officers in the British Army tended to be from the upper class, and usually obtained their ranks by purchase. While this system may seem strange to modern sensibilities, its emphasis on social pedigree and education was intended to provide strong leadership with a vested interest in preserving the British Empire. Though highly privileged, these were nonetheless men of dedication and purpose.

Even when serving in the more remote parts of the British Empire, officers brought their upper-class lifestyle with them. Delegation of daily responsibilities left them plenty of time to pursue leisure activities like hunting, fishing and hosting social soirées. Within the Officers’ Quarters, prominent figures of the growing Penetanguishene community were entertained with music, cards and parlour games.

A Mess Man took charge of domestic arrangements for the officers: procuring all necessary supplies, planning daily menus and making the arrangements for social events. A Mess Servant assisted with these tasks as well as other daily needs such as cleaning, laundry and tending fires. Soldiers’ wives could find employment in the Officers’ Quarters as kitchen help or cleaning staff.

The magnificent Officers’ Quarters is the only original building on the historic site and has been fully restored to represent its early years in the late 1830s.

Restoration of Officers’ Quarters

Original construction of the Officers’ Quarters began in 1831, but it was not until the summer of 1836 that the roof was completed, and the building became habitable. The building was constructed from dressed limestone quarried from nearby Quarry Island and was faced on the interior with brick walls that were covered with lathe and plaster. Built to last, the Officers’ Quarters was the largest of all such structures built by the British in Upper Canada and is one of the few 19th century examples remaining today.

For 20 years, the building served as a residence for the officers of the garrison. Although it was built to accommodate three officers, it was usually only occupied by one or two officers, with a Mess attendant and a domestic. One of its most important functions was to entertain the leaders of the garrison and the notables of the region.

Between 2001 and 2007 the Officers’ Quarters were closed to the public to allow a major restoration effort to occur. Archaeological excavations around the building’s perimeter were completed, allowing for the stabilization of the foundations. Following that were restorations to the above-ground masonry. In the interior, generations of lead-based paint were removed, eventually revealing the original colours used on the walls in 1836. These were scanned and reproduced for the restoration and applied once the plaster had been replaced. A few modern amenities were added to allow the building to meet modern-day building codes. It was reopened to the public in July of 2008.

Aftermath

In 1856, the base was shut down entirely. From 1859 to 1903, the buildings were transformed into a juvenile boys’ reformatory. In 1953 archaeologist Dr. Wilfrid Jury raised the hull of HMS Tecumseth from the bottom of Penetanguishene Bay, and it is now on display in the modern HMS Tecumseth Centre.

Aftermath

The continuing peace with the Americans and further financial pressures back in England eventually took their toll on the military presence in the Canadian colonies. The gradual withdrawal of regular British troops meant that alternate methods of manning frontier posts were required. To this end, the Royal Canadian Rifle Regiment was formed, a detachment of which served at Penetanguishene from 1846-51. However, even this expense could not be maintained, and in 1851 the garrison at Penetanguishene was left to the care of a small number of military pensioners. In 1856, the base was shut down entirely, and another era had come to its end.

Following its closure, the Military Establishment’s lands and remaining buildings were turned over to the Canadian government. In 1859 the base was transformed into a juvenile boys’ reformatory, which operated until 1903. The following year the property became a hospital complex, which gradually developed into the modern Waypoint Center for Mental Health which now stands on the hillside overlooking the original naval and military properties.

In 1953 archaeologist Dr. Wilfrid Jury raised the hull of HMS Tecumseth from the bottom of Penetanguishene Bay. After resting in many locations on the historic site, her remains are now on display in the modern HMS Tecumseth Centre. 1991 saw a major redevelopment of the South End of the property, and in 1994 the entire complex was renamed “Discovery Harbour”.

Thank you for visiting Discovery Harbour and exploring the past with us!

Important Note: The audio recordings for our tours are created using artificial intelligence. While we strive for accuracy, please be aware that the pronunciation of some names may not always be precisely as expected.

Season Passes

For just $35 tax included, season pass holders gain unlimited admission to both Sainte-Marie and Discovery Harbour during their visitor seasons, as well as unlimited admission to most special events at both historical attractions, including First Light and Pumpkinferno!

Special Events

Experience Discovery Harbour in a whole new way; check out our events! Unleash your inner buccaneer at Pirates of the Bay. Dare to explore the unknown during Supernatural Saturdays with spine-tingling Ghost Tours and mystical Secrets of the Seance. And more!

Captain Roberts’ Table

Discover delicious, freshly prepared dishes in a warm and inviting atmosphere at Captain Roberts’s Table. Whether you’re craving a hearty meal or indulging in the famous Sunday Brunch Buffet—featuring the best Eggs Benedict in town—this is the perfect spot to gather and enjoy.